Mount Everest: A Dream Destination with Deadly Consequences

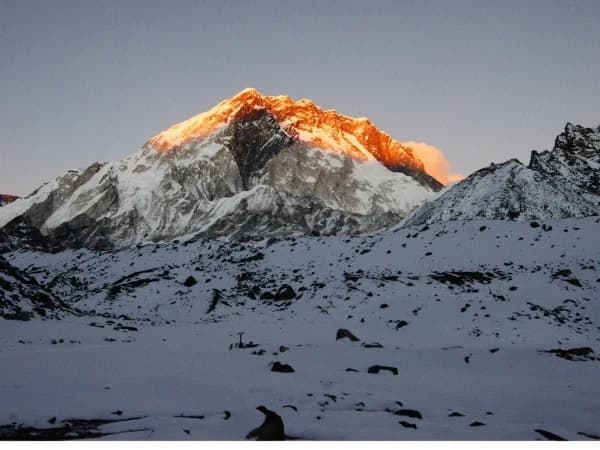

For decades, Mount Everest has captured the imagination of adventurers around the world. Rising 8,8848 meters (29,029 feet) above sea level, standing as the highest point on the Earth, this grand mountain peak is more than a geographical wonder; it represents ultimate challenges for climbers. Each year, thrill seekers, professionals and dreamers from across the world travel to Nepal and Tibet, who are drawn by the idea of standing on the roof of the world. But many don't fully realize that the path to the summit is also a path through life-or-death decisions.

After the first successful ascents in 1953, thousands have reached the summit, but over 300 have lost their lives on the mountain. The numerous and deadly risks are sudden avalanches, sheer ice walls, crevasses which are hidden beneath snow, rapidly shifting weather and the most significant one is the lack of oxygen.

Climbing above 8,000 meters puts the human body in survival mode; it is known as the Death Zone for a reason. At this altitude, the air is too thin to sustain life for long and enormous efforts are demanded in each movement. Here, climbers can lose focus, misjudge distance, or succumb to exhaustion or all within minutes, despite having proper acclimatization and gear; nature often has the final word.

In this unforgiving environment, many climbers have perished and their frozen forms are part of the mountain's memory. “Everest Dead Bodies” is not just a tragic headline; it is a constant reality and their presence serves both as a warning and a tribute, silently reminding others of the unforgiving nature of the mountains.

Mount Everest bodies are not just statistics, actually, they are individuals with stories, dreams and families. But, sadly the same mountain which inspired them became their final resting place.

Why Dead Bodies Are Left on Everest?

Climbing Mount Everest is an extraordinary feat that comes with extreme risk. If a climber dies high up on the mountain above 8,000 meters, which is also called the Everest Dead Body Zone, there is no possibility of bringing that body down. Many of us wonder why the bodies of fallen climbers are not retrieved. The answer lies in a brutal combination of physics, altitude and survival.

Above 8,000 meters, every breath is a struggle. Climbers need to battle with fatigue, hypoxia and freezing temperatures. At that moment, even lifting a backpack feels like moving a boulder. Let's imagine trying to carry or drag a frozen human body, which often weighs over 100 kg in its gear bringing it down through steep ice walls and narrow ridges, which is an almost inhuman task.

Even for skilled Sherpas, who are among the most experienced high altitude workers in the world but the danger involved in a body retrieval mission is immense and several have died in the attempts. So it is the reason why most are left behind and their bodies become part of the landscape, although sometimes respectfully covered in snow or gear and other times exposed by melting glaciers.

There is also the high cost to recover a body and recovering a body from Everest can cost between $30,000 to $70,000 or more sometimes. For many grieving families, it is either unaffordable and ethically unacceptable to risk more lives.

In many ways, the mountain decides who stays. The Mount Everest bodies frozen in ice serve as permanent markers and stark reminders of the fine line between ambition and tragedy. On the Death Zone, even the strongest climbers become vulnerable and for some, it will be the final destination.

Rainbow Valley: The Graveyard in the sky

A hauntingly named place is Rainbow Valley, which lies just below the summit of Everest, on the north side near the final ridge. At first glance, the name may sound beautiful, poetic, but the actual reality behind it is more chilling.

Rainbow Valley gets its name not from being natural beauty but from the colorful down suits, oxygen cylinders and gears scattered across in snow. These bright flashes of red, blue, yellow and green belong to the dead bodies of Everest climbers, and many of whom died within sight of the summit. This valley is a narrow stretch just below the northern route where numerous climbers have fallen to their death or collapsed from exhaustion and never to rise again.

In this region, where the air is razor thin and the temperature can drop below -40°C, survival is measured in minutes. Those who died often remain where they fall, preserved in ice and become part of the landscape and some are lost in crevasses. Others are visible from the route in silent figures in vibrant clothing, who once symbolized hope and ambition.

Climbers passing through Rainbow Valley often speak of the surreal experience while stepping past bodies that they have read about in books or seen in documentaries. Some are used as landmarks helping others navigate the path, which is a sobering reminder that nature is not man but has the final word on Everest.

Everest dead bodies inside the Rainbow Valley stand as a ghostly tribute to those who dared to touch the sky and they are not forgotten, representing personal stories, final dreams and sacrifices made in pursuit of greatness.

The Everest Dead Body Zone: What is It and Where is It?

Death Zone, the term may sound dramatic, but for climbers on Mount Everest it is a chilling reality. This zone begins at 8,000 meters, where the oxygen level is low to support normal human function for long periods. Above this line, the body begins to slowly shut down, no matter how physically fit or experienced climbers are.

It is not just a term used on Everest that applies to many high-altitude peaks, but Everest's Death Zone is especially notorious due to the sheer number of people who attempt the summit and the unpredictable conditions they face. Unlike other lower slopes, where climbers can recover from exhaustion and weather out storms but the Death Zone doesn't offer such mercy.

The body starts using oxygen faster than it can be replenished, leading to altitude sickness, hallucinations and irreversible physical collapse. It is the zone where most climbers make a final push to the summit and many take their final step as well.

Key locations within this zone include South Col, the Hillary Step and parts of the northeast ridge, which are all notorious for sudden weather shifts and dark bottlenecks. In this stretch, many dead Everest climbers remain visible, often lying just feet away from the main trail.

It is just not the height which makes this region treacherous, but the psychological pressure makes and climbers often exhausted, low on oxygen and so close to the summit they even ignore warning signs. In this blind zone of ambition, the mountain quietly takes its toll.

Famous Case of Fallen Climbers

Behind every name on Everest is a name and story, some of these stories have gained worldwide attention not because they were tragic but due to the harsh choices and realities climbers face near the summit.

The most well-known is the body referred to as Green Boots, believed to be Tsewang Paljor Indian climber who perished in 1996 during a violent storm. His body, curled in a limestone cave along the northeast ridge, became a landmark for years. Climbers would pass by him on the way up, bright green Boots earning him his name for over two decades. His presence raised uncomfortable questions about morality, memory and mortality on the mountain.

Another haunting case is that of Francys Arsentiev, the first American woman to reach the summit without supplemental oxygen in 1998. She made it to the top but never made it back. Stranded and severely weakened, she died during descent while her husband Sergei Arsentiev tried desperately to find and help her, but later he also perished on the snow. Francys became known as “Sleeping Beauty,” her body rested just below the summit until it respectfully moved later.

David Sharp, a British climber, died in 2006 after becoming incapacitated near a rock shelter. What made his story so controversial was that multiple climbers passed him on their way to the summit, assuming he was already dead or unable to help. His death sparked global debate about ethics on Everest, should the summit dreams outweigh saving a life?

The Map of Death: Where the Bodies Lie?

Mount Everest is mapped in astonishing detail from glacial crevasses to summit route, still, there's an unofficial layer to this geography that marks the resting places of those who never made it back. Though not published on standard trail maps, experienced Sherpas and high altitude guides are keenly aware of these sites. They have seen them after a year of familiar faces frozen in place, unmoved by time or weather.

Dead bodies on Everest are found in specific zones more frequently than others. South Col on the Nepal side is a key staging point for summit attempts and a location where many climbers have died from exhaustion or exposure during descent. Another hotspot is the Hillary Step, now an altered section once considered the final major obstacle before the summit. Several fatal falls occurred in this area due to the bottleneck, rockfall and fatigue.

On the North side, bodies are often discovered near the northeast ridge and around the Second Step, a dangerous rocky cliff that demands technical climbing skills. Below these areas lies Rainbow Valley, where fallen climbers accumulate when they slip off summit routes or collapse during descent.

Modern GPS technology and satellite imaging helped climbers better prepare for these danger zones and some online platforms have started tracking unofficial coordinates to warn future expeditions. Ethical concerns prevent the formal release of any comprehensive dead bodies on Everest map out of respect for the deceased and their families.

For those who climb Everest, an invisible map is more than a caution. It is actually a reminder that every ridge and slope holds memories, that each marker tells a story for someone who dared to go further than most and paid the ultimate price.

Recovery Efforts: Risks, Costs and Ethical Dilemmas

Recovering the body of a climber from Mount Everest is not just difficult but one of the most dangerous tasks in mountaineering. While some families request the return of their loved ones and harsh reality is that few bodies are ever retrieved, especially from higher sections of mountains.

Bringing down deceased climbers from the Death Zone involves assembling a specialized team, including elite Sherpas who must risk their own lives in the process. The frozen remains often stuff and lodge in snow or rock can weigh over 100 kg with gear. Carrying this weight down steep slopes across ladders and along narrow ridges is not only physically taxing, but it can also be fatal.

Financially, the cost of a recovery mission can range from $30,000 to over $70,000 depending on location, weather and logistics. Helicopter retrieval is often not an option at extreme altitude. In most cases, especially when the body is located above 8,000 metres, recovery is deemed too risky to attempt and there's also an ethical dilemma: is it right to endanger more lives for a body? Many climbers accept the risk of death before their ascent and express a wish to remain on the mountain if things go wrong and for some, Everest becomes a grave of choice.

These dead Everest climbers are not forgotten, whether recovered or not, they are remembered by fellow mountaineers and honored as part of Everest's enduring legacy as a reminder of the courage and cost of reaching the top of the world.

Climbers' Perspectives: Facing Death on the Way Up

To those who dared to climb Mount Everest, encountering death is not just a distant possibility but often a visible reality. Many climbers have spoken openly about the emotional weight of passing frozen bodies on the ascent. These aren't just nameless figures but a reflection of what could happen if things go wrong.

Some describe the experience as surreal. Mount Everest bodies still wearing their gear, boots pointed towards the summit, is a sobering moment and they are reminders that the line between success and tragedy is razor thin at high altitude. Even the best prepared can become overwhelmed by altitude sickness, frostbite or exhaustion in the final stretch.

Yet for many, the presence of these bodies doesn't deter the mission; instead, it sharpens focus. Climbers speak of moving in silence, acknowledging the fallen with a glance or whispered prayer before pushing forward. There's an unspoken code on Everest: don't interfere unless there's a chance to help, because staying too long could mean joining them.

Others admit to guilt and survivors return haunted by the memory of stepping past someone in distress. But when survival is at stake, judgment becomes clouded at such heights that heroism is sometimes impossible.

For many Everest veterans, the presence of the dead is not just a warning; it's a rite of passage. To climb Everest is to walk a trail shared with those who came before and in those moments, the mountain feels heavier not just with snow but with memory.

Modern Solutions: Is There a Way to Clear Everest?

The question of removing the dead Everest climbers from the mountain is one that sparked international debate. In recent years, tourism and climbing traffic have increased. There's been growing pressure to address the visible presence of bodies on Everest's slope, but solutions are far from simple.

Efforts have been made to organize a recovery mission led by experienced Sherpas and supported by the Nepalese government. In some rare cases, climbers who remain have been brought down and returned to their families. These missions remain expensive, dangerous and logistically complex, especially above 8,000 meters, where the risk to rescuers is extreme.

To counter these challenges, modern tools are beginning to play a role. Drones, for instance, have been tested to survey bodies, assess potential retrieval routes. An Advanced GPS System can track climbers in real time, increasing the chance of an early rescue rather than late recovery.

Some have called international mountaineering organizations to create protocols for body removal, but no formal global policy exists. Now, the mountain remains largely as a resting place for those who never return. Technology may offer hope, but Everest's silence still speaks louder than innovation.

Conclusion: The Price of Glory on the Roof of the World?

Mount Everest is more than a mountain; it's a symbol of human ambition, endurance and the eternal pull of the unknown. But, along its ridges and beneath its summit lies a colder, darker truth: the mountain also keeps what it claims.

The presence of Mount Everest bodies scattered across ice fields and frozen into ridgelines reflects the sheer cost of attempting to reach the top of the world. Reasons behind leaving bodies behind are complex, which are rooted in ethics, survival and the raw impossibility of recovery in such hostile conditions. Yet their presence serves a purpose, marking the boundaries of human effort, danger of summit fever and the line between determination and fatal miscalculation.

As Everest continues to draw more climbers each year and also continues to whisper the stories of those who never returned. To honor them is to remember their courage, understand the risk and walk in the mountain with humility.

“ Beneath the silence of Everest lies a chorus of unfinished dreams which are frozen not in failure but in fierce pursuit of the impossible”.